An Analysis of the Wage Gap in Pierce County

January 28, 2021

INTRODUCTION

At WorkForce Central, our aim is to increase economic vitality for all Pierce County residents. Like many of our partners, we share the goals of increasing access to living-wage jobs and cultivating a strong economy. While this collective vision is strong, we also know it is incomplete, as these goals are often achieved with disparate outcomes. This report demonstrates how wage disparities by gender and race show up in our Pierce County economy and highlights steps employers can take to shift policies and practices that perpetuate these gaps. It is by no means a complete picture of local wage gaps or of the multifaceted ways we can address them. The narrative and data that follows is an effort to add to the ever-growing body of evidence that these inequities persist and that the power to combat them begins with us.

The wage gap is an equity problem, albeit a complicated one. Workers receiving lower rates of compensation along gender and race lines is a clear note of injustice and is one of the most obvious and measurable forms of disparity. The way these gaps are created and play out, however, often blurs our sense of justice and confounds our resolve to address it. The wage gap is complicated. It is full of nuance that requires our collective time and consideration to unpack. We aim here to explore this issue as it stands in Pierce County, Washington. Our analysis takes a closer look at the nuances in the story and the data to better understand the drivers of the wage gap and identify solutions within that context to effectively address economic injustice.

ANALYSIS

Perhaps the most obvious challenge to this analysis is that the information is based largely on pre-pandemic data. Since Mid-April 2020, the proportion of continued unemployment insurance claims from women has grown in Pierce County from 45% up to 51%, suggesting that women may be disparately impacted by the pandemic, much like we are beginning to see in national labor statistics (Current Population Survey). We also know that the greatest concentration of jobs lost over the pandemic had a lower average wage. While we don’t know what the overall impact of the pandemic will be on the wage gap, there is a potential that we will see an artificial bump in median wages and – considering disparate job loss by gender – an artificial decline in the gap as well. Given multiple factors that continue to blur the impact of the pandemic on jobs, wages, and our local economy, it may be years before we can fully measure the impacts of COVID on the wage gap in Pierce County. While that may be, we don’t need to wait years to understand the challenges that are evident now.

The Gender Wage Gap

What is the wage gap? At the highest level, the gender wage gap is the relative difference in earnings between women and men. This can be measured in different ways and adjusted for a number of factors. One specific framing is pay inequity which is essentially the adjusted difference in wage for the same job. While still a very persistent challenge, pay inequity represents a factor of declining significance in the overall picture of the wage gap (Cohen 2013). When considered in workforce and economic development circles, the gap is typically presented with a lens that focuses on people who work full-time and year-round. In Pierce County, that gap is 0.79. In other words, for every dollar earned by men in Pierce County, women earn 0.79 cents. This framing, however, excludes the differences in the concentration of workers in gig or part-time jobs (often holding more than one and working more than 40 hours), and workers in seasonal positions, and those who have to leave employment for family or medical reasons. For this report, we chose an unadjusted approach, looking at all workers, to capture the overall effect of these drivers and to provide granular regional comparability.

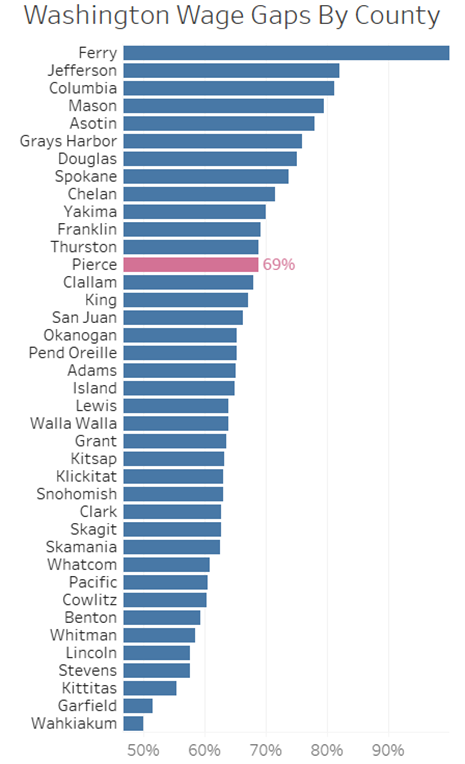

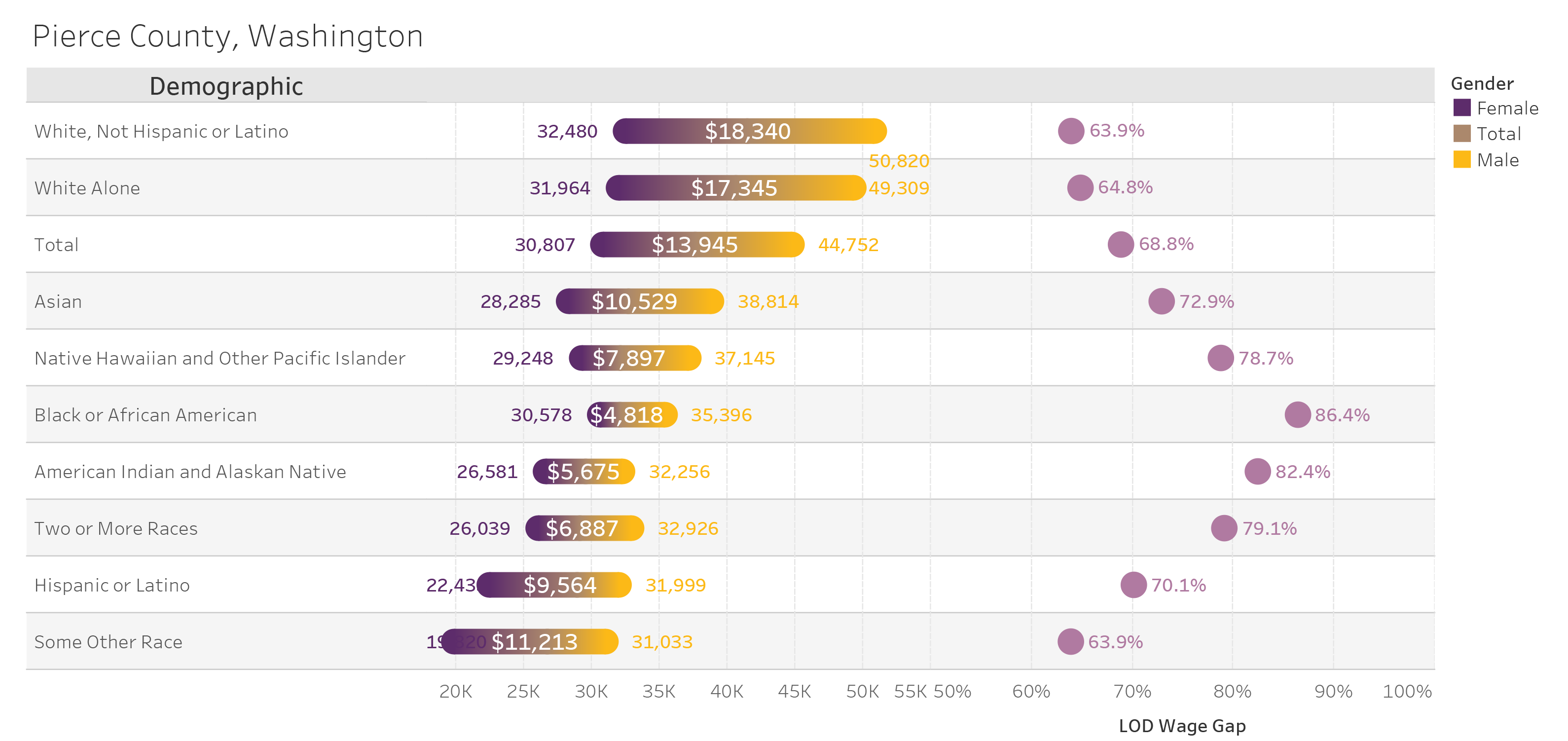

In Pierce County, the total wage gap is 0.69. For every dollar earned by men, women earn 0.69 cents. This is a useful measure for comparing regions, but more often, we apply the wage gap to make other comparisons within a region’s workforce (i.e. by demographic groups, occupations, industries, etc.). In addition to the relative difference, we also report the absolute difference for more context and to give a more meaningful representation of that gap.

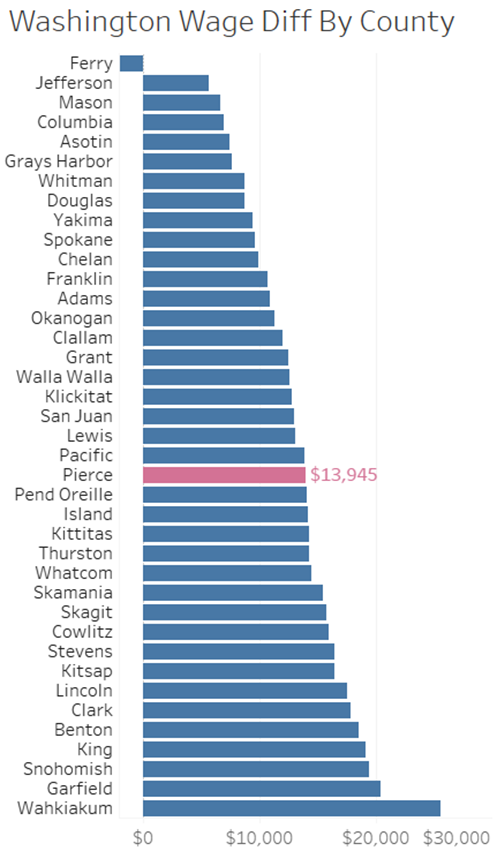

In Pierce County, the wage difference (i.e. difference in median earnings between men and women), is $13,945 annually. The absolute difference has the distinction of feeling more approachable, as having a dollar sign anchors the number to reality, giving a clue to how that difference might feel for those affected. The wage difference is far from consistent person-to-person. After all, it’s only the difference in the middle wage between two groups of people. For about half of working women in Pierce County, the difference in pay is less than $14K, but for just as many the gap is even greater.

Across the state of Washington, the wage gap varies significantly, from 0.5 in Wahkiakum County to 1.08 in Ferry County. At 0.69, Pierce County ranks 13th in the State. When ranked by overall wage difference in dollars earned between women and men, Pierce County slides to 22nd.

Looking at the wage gap across the US, Pierce County falls in the 58th percentile, cementing our region’s place in the middle of the pack.

Closing the wage gap in Pierce County would require a median pay raise of 45% for women (or a median increase of $13,945). Over a typical 40–year career this difference would translate to well over half–million dollars.

The Intersection of Gender and Race

We know wage gaps are not as simple as the differences we see between men and women. Taking a closer look at the gender wage gap in Pierce County, we see significant differences by race. The gap is widest between those identifying as “White, Non-Hispanic or Latinx” and those identifying as “Some Other Race” (64%). We also see big differences in pay between men and women by race, with the smallest gender pay difference occurring among Black and African American workers ($4,818).

White men are paid more than any other demographic group of men or women.

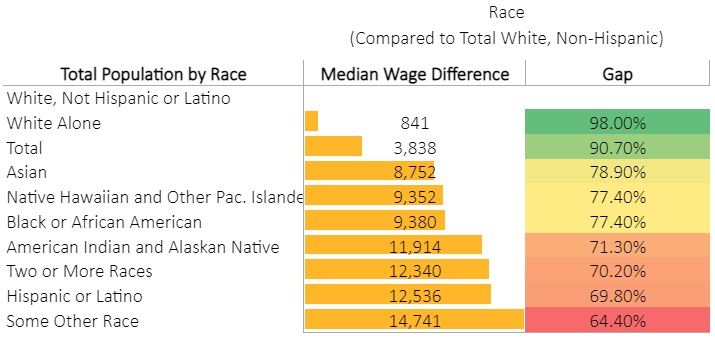

When we ignore gender and compare racial demographic groups with the highest-earning group (White, Non-Hispanic or Latinx), the wage difference by race and ethnicity ranges between $8,752 (among Asian workers) up to $14,741 (identifying as “some other race”).

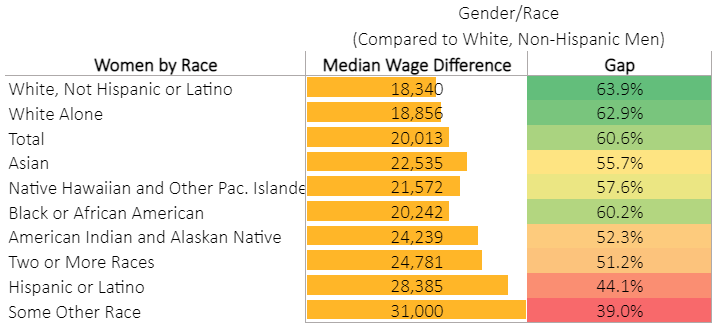

Further refining the baseline to the group with the highest average income (White, Non-Hispanic or Latinx men), we can measure the gap as it is compounded by both gender and race. When compared to white, non-Hispanic men, the wage difference increases to a range of $18K up to $31K, with women of color making at or below half the median wage of white men (between 0.39 and 0.60 cents for every dollar earned by men).

Gender and Race Gaps by Job Type

Nationally, the wage gap by gender has been shrinking for the past three decades (Pew Research Center). In that period, there have been significant increases in workforce participation and in the proportion of women earning a college degree, but gains have been muted by persistent gender-based divisions of labor with consistently less pay for the jobs more frequently held by women.

For the purposes of this report, gender segregation is the difference in the proportion of women to men by job or industry. This form of gender disparity continues to be the primary driver of the wage gap. Prominent researchers on this topic, Blau and Lawrence Kahn, found that from 1980 to 2010 the effect of gender segregation on the wage gap rose from 20 to 51 percent (2016). While pay inequity persists as a core issue, gender segregation by job or industry is the greatest contributing factor to the overall gender wage gap.

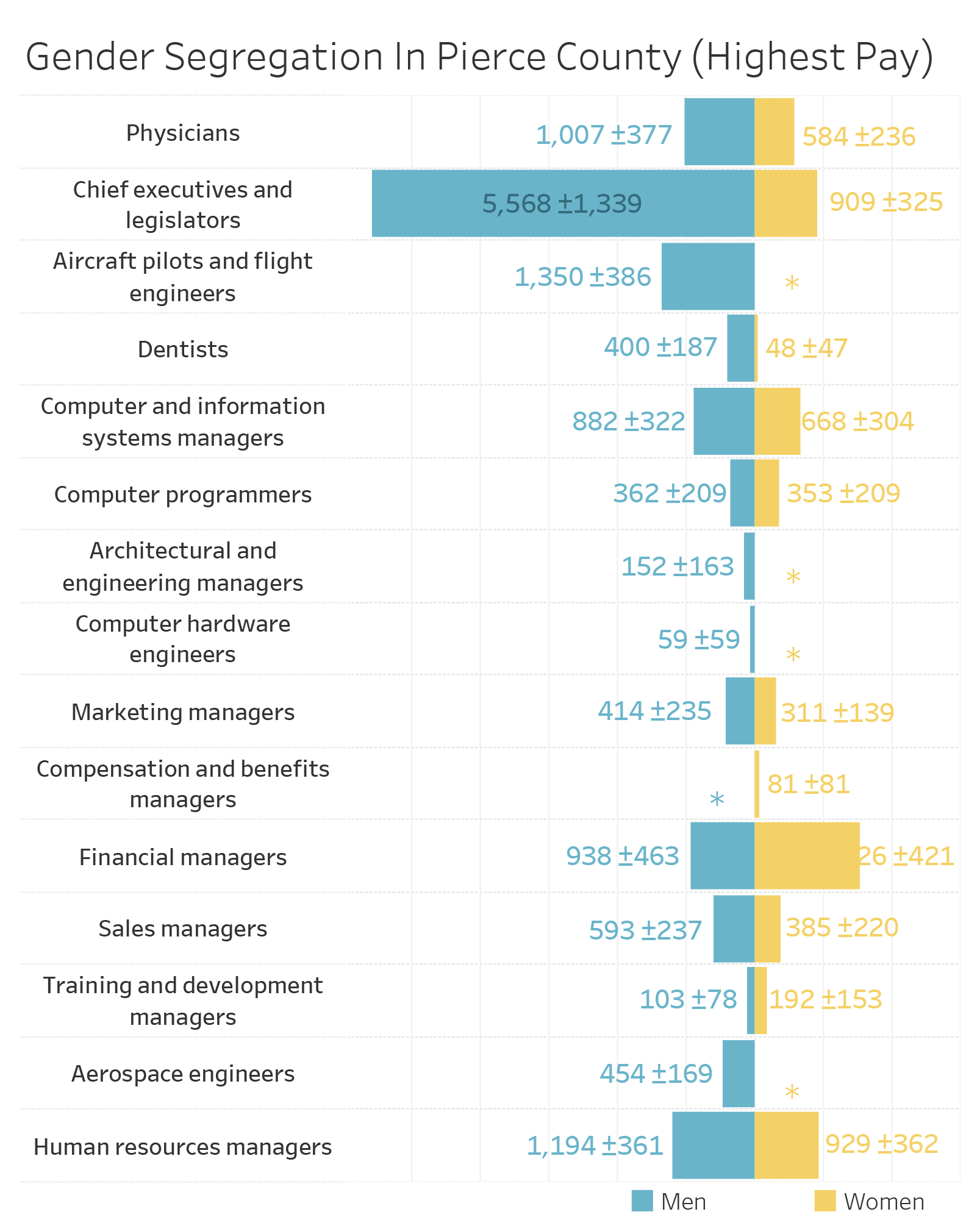

Gender segregation is a significant issue within the Pierce County labor force. Looking at the highest wage jobs in the region, we see that a clear majority are held by men. Among the few cases of high paying fields where women are in the majority (Compensation & Benefits and Training & Development Managers), we see that the number of women employed in these fields is relatively small (81 and 192 respectively). Chief executives and legislators – those with the greatest capacity to enact change – represent the largest share of highly compensated jobs (6,477), but only 14% of these are held by women. Among the top 15 highest paying jobs, men hold 69% of these positions in Pierce County.

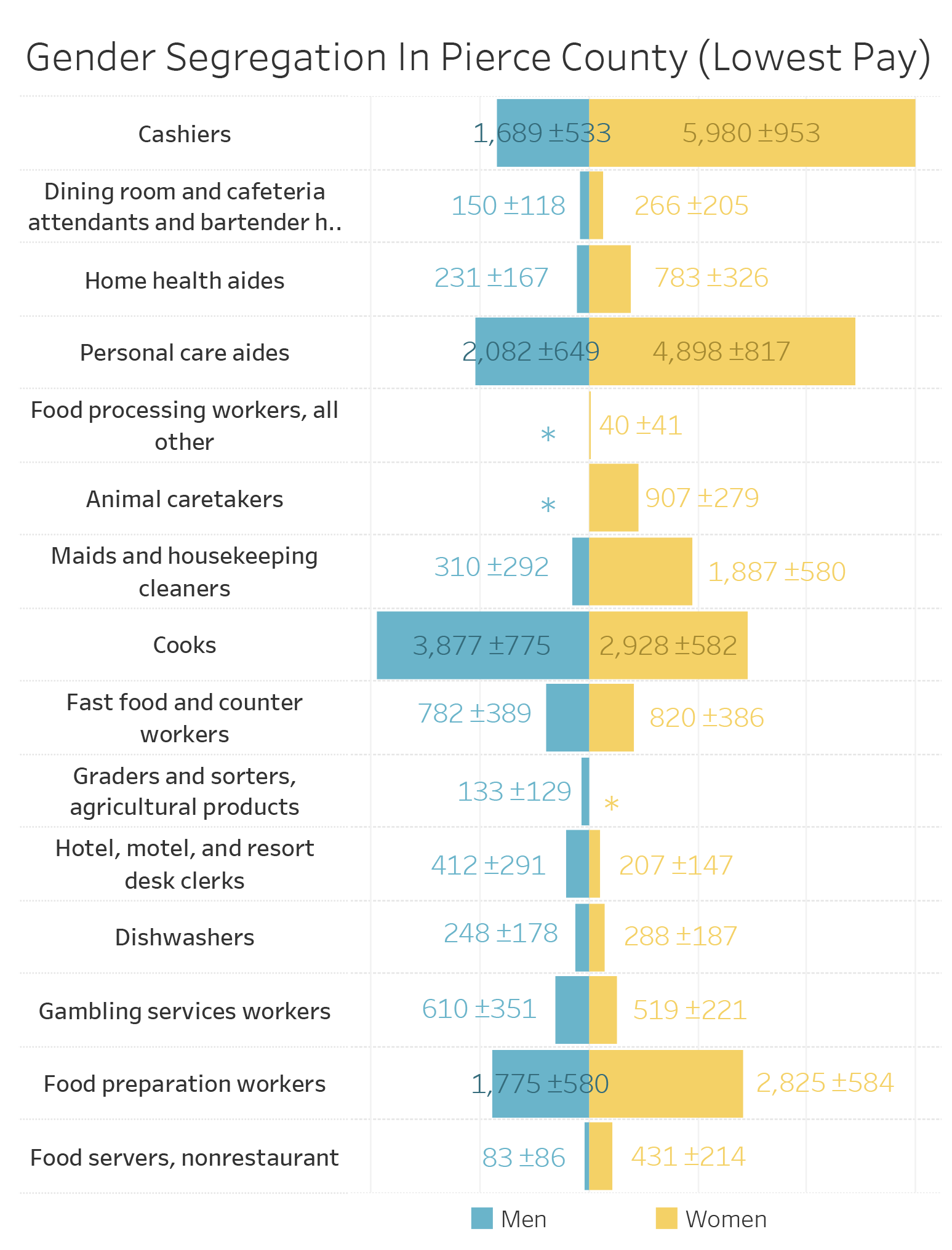

Occupation estimates are reported for each gender along with 95% confidence intervals. * indicates a census estimate suppression.

Even more troubling is gender segregation within the lowest wage jobs at the other end of the spectrum. Not only are there significantly more low paying jobs in Pierce County in general, but nearly two out of every three are positions held by women.

Put simply, women are less likely to work in highly compensated jobs while also being more likely to do the jobs that pay the least.

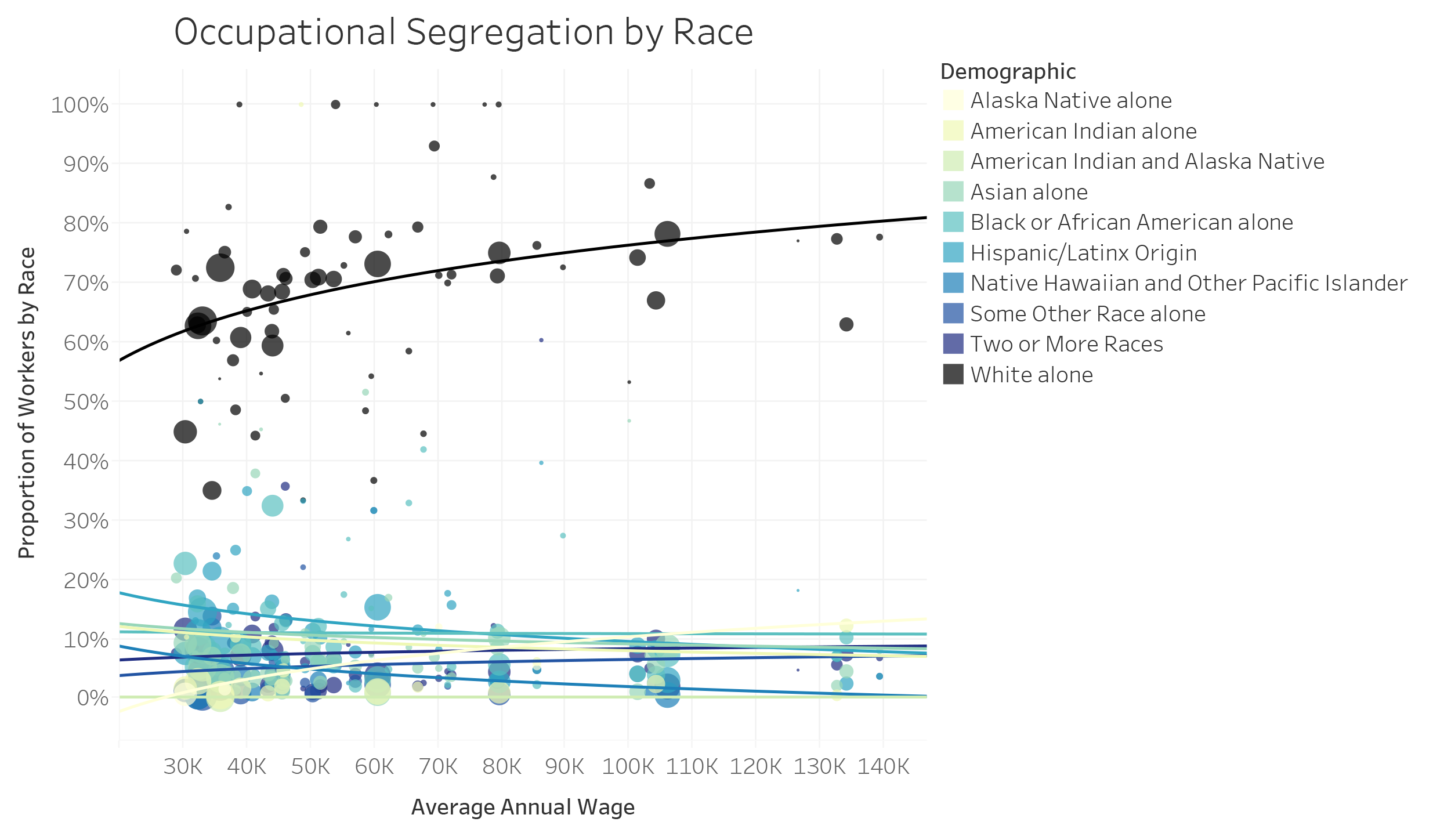

Significant occupation segregation also occurs by race. We see a murkier association with wage, but on average, higher wage occupations are more heavily held by those identifying as “White, Non-Hispanic”. Though less stark than the differences by gender, this trend is significant for broad occupation groups in Pierce County. In the graph below, we see that white workers make up the majority of occupations across the wage spectrum. We also see, however, that they make up a greater proportion of those holding high-wage jobs while people of color make up a smaller proportion of those individuals. This is indicated by the line indicating an increase in proportion for white workers as wages increase, and a downward or static trend for workers of color as wages increase.

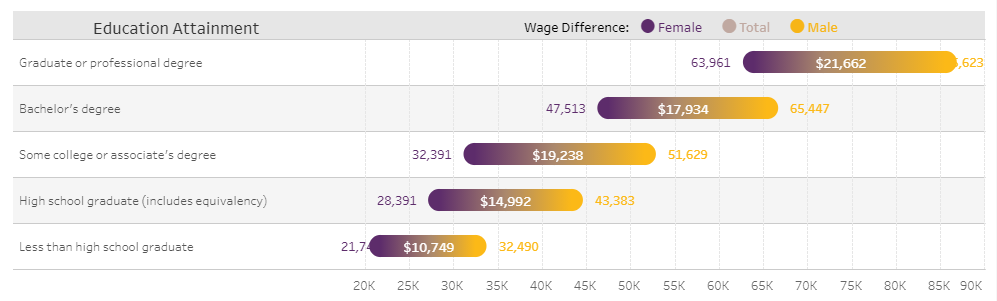

Higher education attainment leads to a reduction in wage gaps, with a smaller gender wage gap among those with a bachelor’s degree or higher (.73 and .75 respectively). Still, it’s striking that the median wage for men in Pierce County without a high school diploma is higher than the median wage among women with some college or an associate’s degree. Among women who earn a graduate degree, the median pay is $1,486 less than men with a bachelor’s degree and $21,662 less than men with a comparable level of education.

The Pandemic and “Women’s Work”

If the recent pandemic has taught us anything, it is that caring for children, cleaning, the provision of food, and all the additional responsibilities that have traditionally been considered “women’s work” can no longer be taken for granted. Over half of workers designated as essential are women, yet those essential jobs are typically paid well below the median hourly wage (average hourly pay for cashiers is $13.29; for childcare workers $14.61; for health support workers $15.33). The demand of “equal pay for equal work” alone overlooks the overwhelming reality of occupation segregation by both race and gender and needs to be accompanied by a clear examination of the cultural and historical foundations behind the sorting of men and women by occupation.

CALL TO ACTION

Eliminating wage disparities by gender and race in Pierce County will take collective action from individuals, employers, economic and workforce development systems, and policymakers. We strongly believe that our region can lead in reducing wage gaps across our workforce while increasing access to living wages. As we continue to learn and grow, WorkForce Central is integrating the following evidence-based recommendations into our policies and practices. If you are an employer, we urge you to consider how you might also approach this call to action to shift the persistent reality of wage disparities toward one of economic prosperity across gender and race in Pierce County.

Recommendations for Employers

Set the wage for the job, not the person: Avoid prior salary history when setting current pay. This practice can unintentionally perpetuate past discrimination from previous employers. To avoid potential past wage bias, we encourage employers to not ask for past wages. If employers are hiring with a wage “based on experience”, avoid bias by setting a clear pay scale with set levels of experience at the beginning of the process and stick with it.

Share the wage: Publish the set wages or wage range with job postings from the beginning and be open and clear about wages across the organization. According to a recent report by Payscale, this demonstrated commitment to transparency has proven to be a significant indicator of reduced and in some cased eliminated wage gaps within businesses and organizations.

Mind the gap: Default to curiosity as opposed to suspicion when you notice a gap on someone’s resume. When hiring, we have been conditioned to consider a gap in paid work as an indicator of failure or something amiss. People have gaps in paid work for any number of reasons completely unrelated to their ability to perform or excel at the position you may be looking to fill. Examples include taking time off to care for children or a family member, something women are more likely to do than men, and something that requires a highly valuable skill set, or downsizing prompted by COVID. Someone may have taken time off to improve a skill set that is right in line with what you are looking for, like learning a new language or getting a certificate. There are any number of reasons a job seeker might have a gap on their resume. It likely isn’t a sign of failure at all and may even be what makes a candidate a perfect fit for the role.

Measure the differences: Most employers don’t know what the level of inequity is within their organization or business. Measuring compensation differences and job representation by gender and race is the easiest way to understand the issue and its scale. Start by asking if your work is segregated by job, wages, or management level. Are there noticeable differences in concentration by gender or race? This will give you an honest assessment of your baseline and help you understand where you need to focus.

Market broadly: Understand where disparities exist between and within jobs at your business. Take action to ensure that postings are effectively marketed to segments not well represented in your company. Include language in postings to ensure you’re not only encouraging but prioritizing candidates who bring different perspectives and lived experiences to your team. Check the language in position descriptions (and have others review it also) and consider whether it would be understood by someone who might not be an obvious first choice or who doesn’t come from within your industry. Set interview requirements to ensure that a diverse pool of candidates is considered for every hire.

Value lived experience: Individuals who experience the world through a different lens based on their race and/or gender identity (or any identity, for that matter) have the potential to bring critical new perspective and value simply by virtue of their ability to understand and see things differently. If you are building a software platform for worldwide use, but only White, English speaking men lead the work from conception through design and production, you are likely to miss key barriers to adoption for whole communities who will approach the product differently. If you’re building a service focused on alleviating hunger, you are far more likely to succeed with people on your team who truly understand that lived experience. The examples of the value of diverse perspectives and lived experience on any team are vast. Consider how you might incorporate that experience as a highly valued skillset for any job.

Check credential requirements: Does the job you’re looking to fill really require a bachelor’s degree, or a graduate degree, for that matter? Sometimes the answer to this question will be yes, but often, this is a default requirement that we set based on the notion that a college degree signifies the potential for higher performance. What specific skills does the job require that come from having obtained a bachelor’s degree that could not be gained through an equal amount of combined work and lived experience? These are important considerations for a number of reasons, a critical one being that students of color often face far greater systemic barriers to college completion than their white peers (Libassi, Center for American Progress, 2018). It is worth considering what is driving the credential requirement in every position you post.

ABOUT WORKFORCE CENTRAL

WorkForce Central carries out the vision of Chief Local Elected Officials and the Pierce County Workforce Development Council by coordinating, administering, and advancing the work of the workforce development system. Their work strengthens the Pierce County economy by identifying skill gaps between jobseekers and employment opportunities, fostering data-driven decision making, and connecting workforce development partners into a cohesive, collaborative, and effective network.