The Experience of Mental/Behavioral Health Providers in Pierce County

February 13, 2023

Introduction

When a group of behavioral health practitioners in Pierce County was recently asked, “What do you wish the public understood about community mental health?” their response was resounding. “Everyone has mental health,” they stated.

“People often have this picture of what kinds of people seek behavioral health services, but it looks like all of us,” one practitioner said.

“It’s not something that’s scary. It’s a basic need that everyone deserves,” said another.

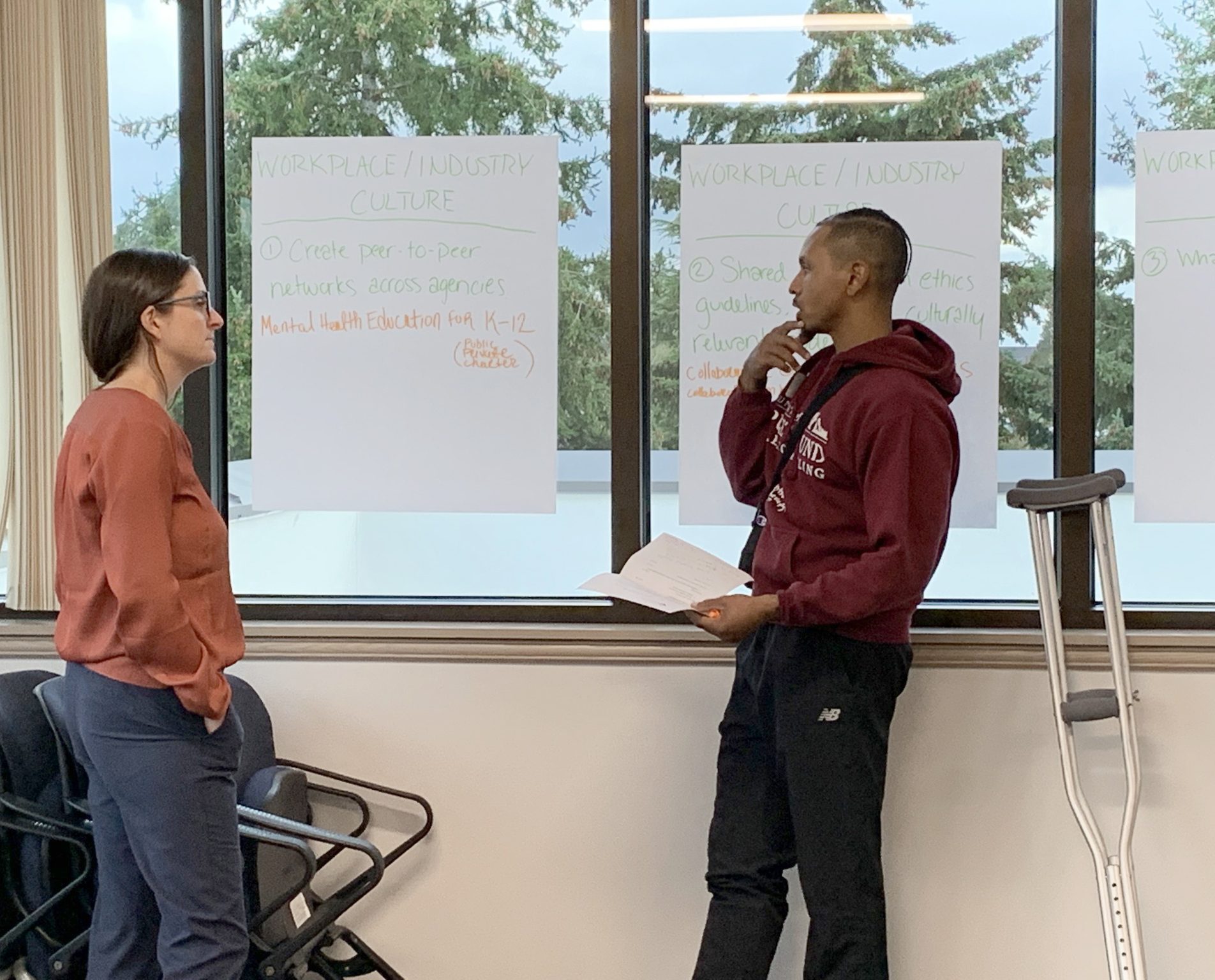

In November of 2022, WorkForce Central convened a group of behavioral health practitioners from across Pierce County to better understand the barriers that exist to entering and progressing in the behavioral health workforce. There is a growing body of knowledge around the inequities and policy changes that are needed to ensure this workforce is truly supported and thriving. However, we also know there is critical nuance that is added to our understanding of these issues when we ask the experts themselves, those with the lived and professional experience of being deeply entrenched in this work every day.

The following is an account of what those local experts in the field had to say about the struggles they themselves or their colleagues have faced in navigating their career pathways in the behavioral and mental health workforce. Overall, while comprised of individuals passionately committed to their work and the communities they serve, the current Behavioral Healthcare workforce is struggling. In many ways, people are overburdened, confused, and find they lack the support necessary to grow and explore pathways toward progression in the field.

Equity in the Workforce

“We need to elevate the respect the field deserves.”

The pathway to becoming a mental and behavioral health professional is complex and involves advanced education, internship hours, and a licensure process. The pay while interning and in the field is not reflective of the time and commitment it takes. Unpaid internships and low wages are two significant concerns when considering how to support and retain workers. Many professionals start out in community behavioral health but frequently leave to go into private practice where they can find higher salaries. There are also factors such as the structure and policies around insurance companies’ billing of Medicare/Medicaid that enable low reimbursement rates for mental health services. Requirements in documentation and paneling forces community mental health agencies to push their workforce to take on higher caseloads, to spend hours on documentation to meet insurers’ expectations, and is a significant contributor to burnout and providers moving to private practice.

Interns are required to complete a set number of hours working in the field under a supervisor. These hours are generally without pay. During our discussions, the professionals we met with shared the struggles they and their peers faced trying to complete their internship hours while also trying to support themselves. One participant we talked with opted to not go into behavioral health after graduation because they found they wouldn’t be able to pay their mortgage and support their family as a single parent. During these discussions, all of the professionals we spoke with expressed interest and support in the idea of providing stipends and/or paid internship hours as a way to better support interns during their licensure process.

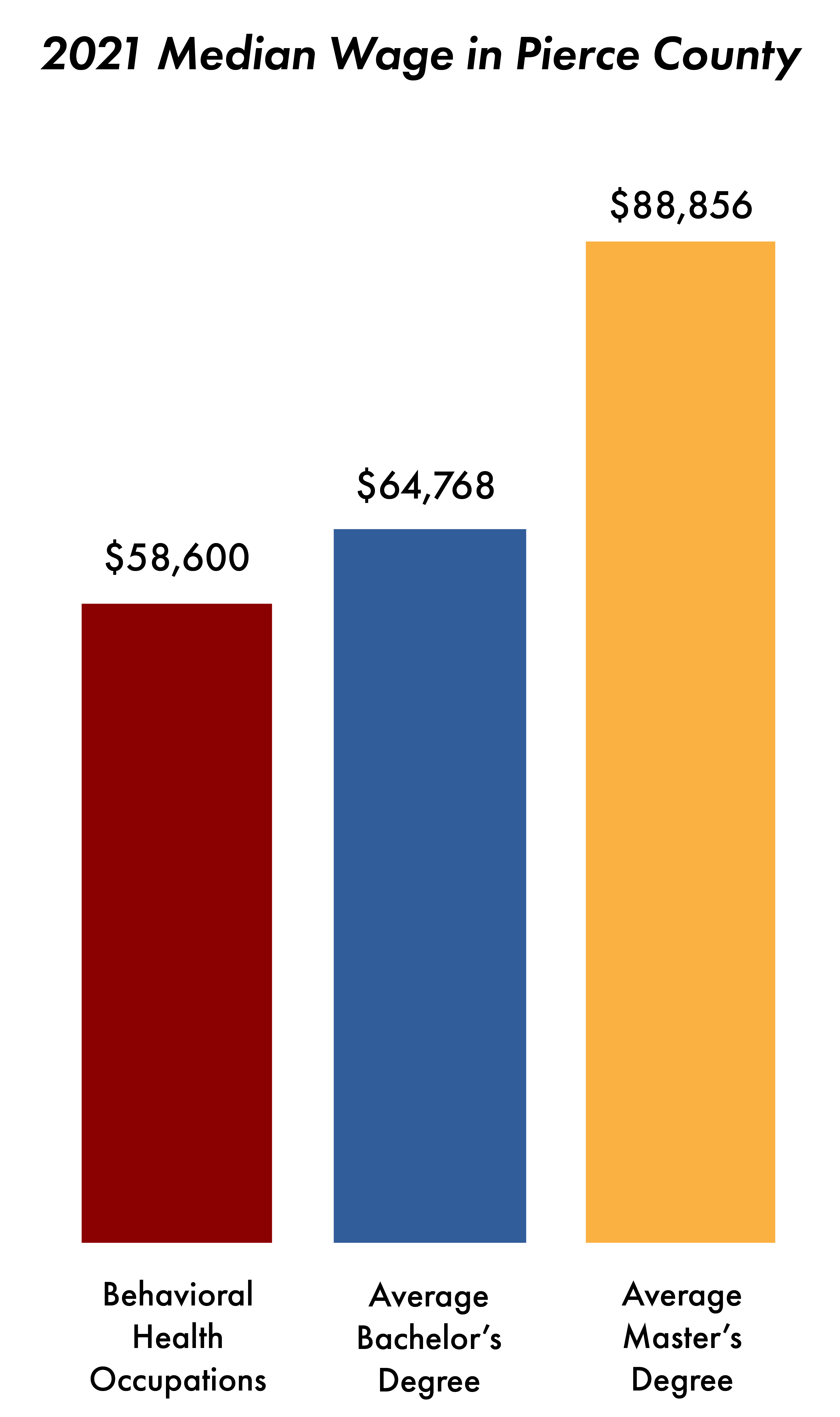

At the same time, mental and behavioral health workers are some of the most highly educated professionals in our labor force. They fall within several occupation categories, most requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher. The cost of education versus the average annual wage among behavioral health workers is a significant barrier to entry and advancement for those considering a career in this field. A new report by the Behavioral Health Workforce Advisory Committee with the Washington Workforce Training & Education Coordinating Board shows that mental health counselors have an average of $145,000 in student loan debt. However, the median wage for these workers in Pierce County was just $58,600 in 2021. This is roughly 10% less than the median wage among all workers with a bachelor’s degree and about a third less than workers with master’s degrees working in other professions.

Perhaps most telling is that, on average, a mental/behavioral health worker could expect a pay raise just by switching careers, as the average annual wage for workers with a bachelor’s degree is $59,300 vs. $61,000 for all workers in other career fields. The education and career pay disparities were clearly reflected in our conversations with these local professionals and were often perceived as a lack of value society places on these careers.

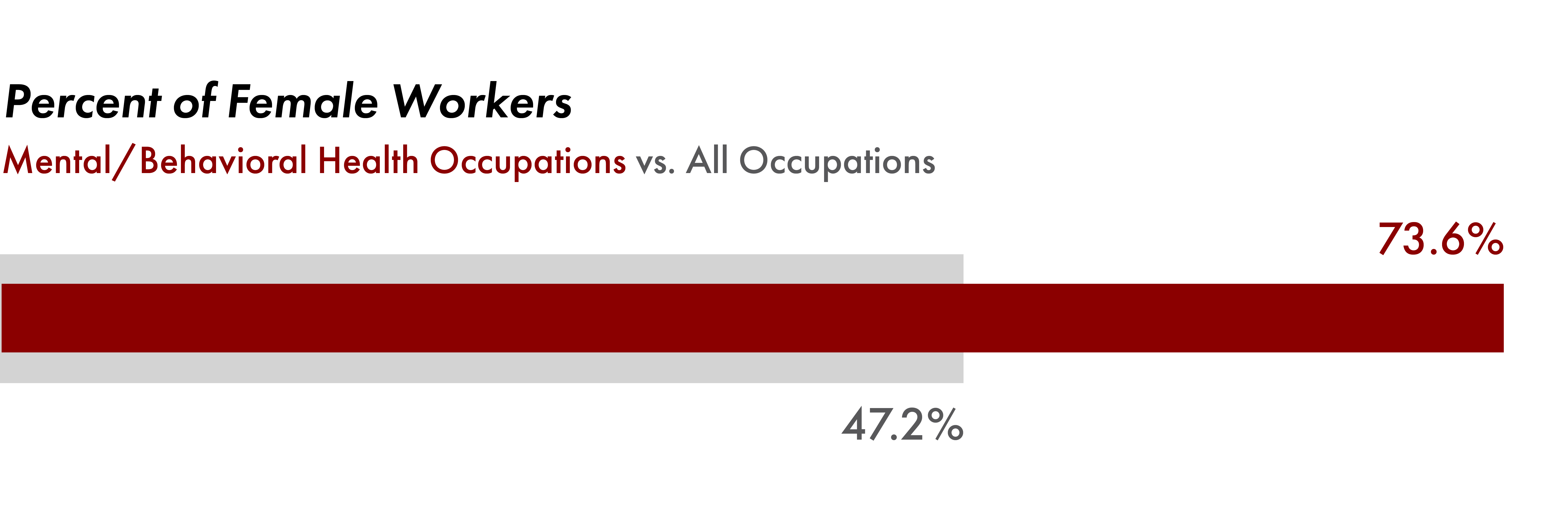

At the same time, inequitable salaries based on education are also impacted by the fact that men in Pierce County received about $13,000 more in wages than women in Pierce County (median earnings for population ages 16 and older with earnings). Put another way, for every dollar earned by men in Pierce County, women earned just 75 cents. However, this disparity is even more exaggerated among workers with post-secondary degrees – men with a bachelor’s degree make, on average, $25,000 more each year than women with the same level of education in Pierce County (2021 ACS). And with women representing three out of every four mental and behavioral health workers in Pierce County, this disparity also greatly impacts pay equity in this field.

Professional Development

“We want supervision with knowledge, competency, and passion.”

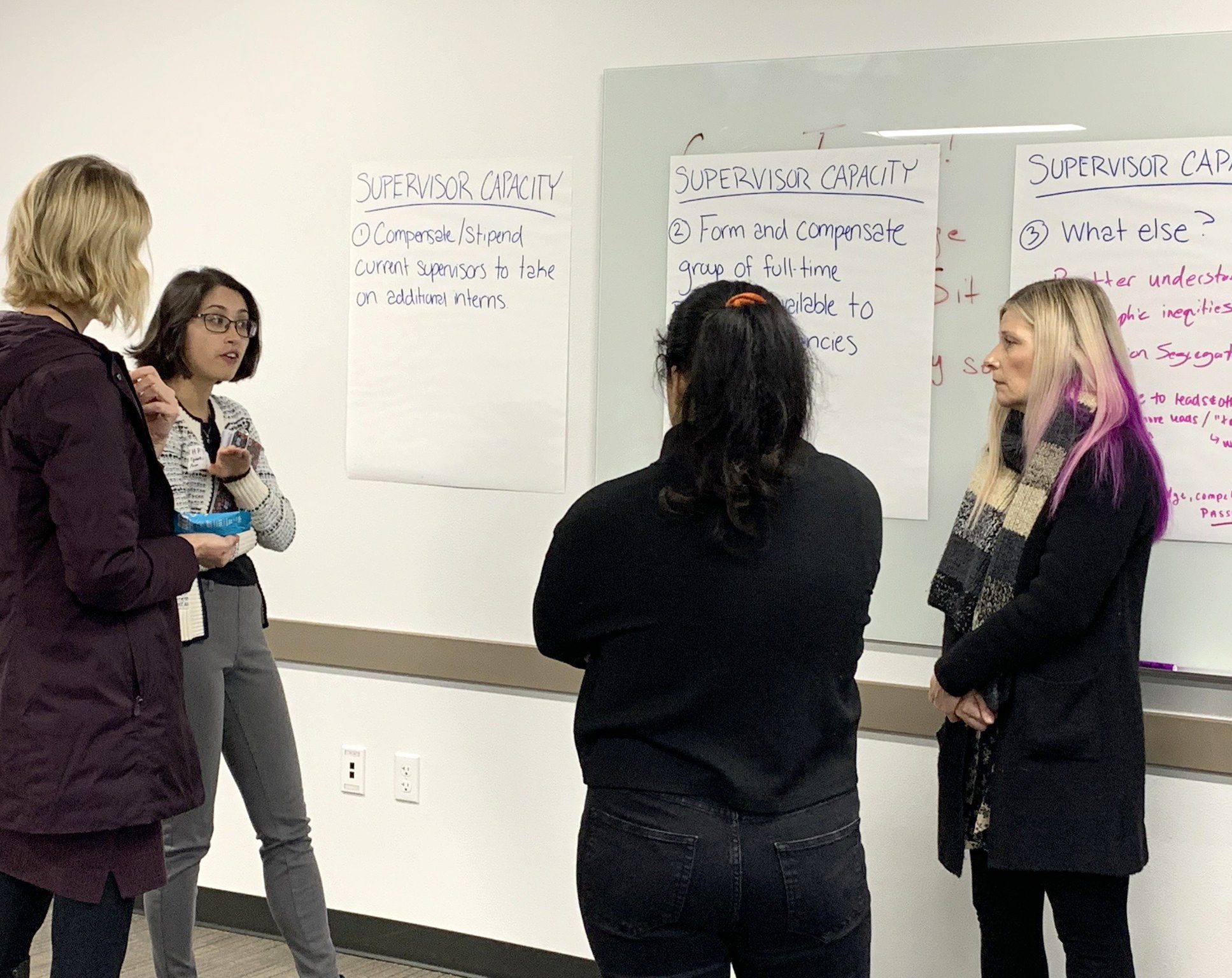

A common theme in our discussions was that mental/behavioral health professionals and interns do not often know where to seek support within the current system. Interns work for little-to-no pay and have minimal supervision because supervisors are overburdened, often working large caseloads themselves. Many practitioners are also reluctant to take on interns because they don’t have the capacity. These professionals would like to see more designated support and put forward the idea of having a shared supervisor whose sole responsibility was to supervise and support interns during their licensing process. Continuing education was also brought up as a struggle, and the suggestion of having designated professional development days, paid for by their employer, was strongly supported.

Defining Clear Pathways

“I don’t know what the next step is. I don’t know where to go from here.”

These professionals also expressed frustration and confusion in how they navigate their careers. They didn’t always have a clear understanding of pathway progression and struggled with understanding the licensure process as well as how to advance in their positions. Behavioral health workers are also unsure of what pathways are available to them within this field. There is no clear career progression ladder as you would see in other healthcare-related fields. The public and private sectors also have their own processes for progression, so it’s not one size fits all model. Ultimately, the uncertainty is also making it more likely that individuals will move on to private practice.

Awareness and Understanding

“Mental Health begins at the start of life. If we invest earlier, we can prevent a lot of what we see.”

While there have been drastic strides as a society to destigmatize mental health needs, the professionals we talked to were confident that, if more is done at an earlier age, many later mental health struggles may not come to fruition. Helping children understand and express their feelings while recognizing signs of mental health struggles in themselves and their peers could have significant impact in easing the burden on the system. While in 2017 Pierce County averaged nearly 60 counselors per 100,000 people, in 2018 it had only 6.5 child and adolescent psychiatrists per 100,000 people. This is far less than the recommended amount from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. There is a need to invest in educating students not only about their own mental health, but by offering high school career and technical education programs that focus on Behavioral Health Tech/Mental Health occupations, paid internships, and programs to support certification/licensing processes.

Recommendations

- Provide more support for behavioral tech workers in schools.

- Continue focus and support for social/emotional learning and whole child development.

- Consider using a health-focused curriculum in schools for peer-to-peer support and development. The Health-Centered Community Schools model acknowledges that school-based clinics can serve children and youth on campus, particularly those receiving Medicaid benefits.

- Increase opportunities for career exposure through Career and Technical Education (CTE) programs, paid internships, and offering college credits for High School students interested in the field.

- Work with regional workforce and behavioral health stakeholders and partners such as community and state colleges, training programs, behavioral health organizations, and other employers to develop standard recruitment and hiring practices.

- Develop materials and processes to help guide the incoming workforce on clear pathways and opportunities in the field.

- Address equity in pay by setting clear recruitment equity goals and clear wage advancement scales. Assess the level of occupational segregation within establishments, and set goals and actions to address it. Employers can also utilize recommendations from our Wage Discrepancy Report.

- Promote and/or expand existing loan forgiveness, tuition reimbursement, and scholarship programs to offer more affordable pathways and ease the financial burden.

- Set standards for a quicker, clearer process for staff to get licensed. Once licensed, providers can bill more to Medicare/Medicaid, which offers incentive.

- Dedicate funding and staff to workforce development through cross-collaboration to provide shared resources for education and retention.

There is no simple solution to removing barriers to access and progression in the mental/behavioral health field in Pierce County, but there are clear opportunities to strengthen these pathways. From more support for primary school behavioral health technicians and further emotional/mental health education to programs to help secondary and post-secondary students learn about the field with clearly defined pathways and processes to get into the field, there is no shortage of opportunity for improvement. The need to explore internship structures and ways to educate students earlier to help them understand their own mental health, but also the opportunities available to get into this rewarding field. For entry-level workers, we need to address the issues leading to confusion in navigating the licensure process. And, especially for licensed and experienced professionals, we need to address the issues leading to burnout and inequitable pay and figure out how we are going to provide a strong system to retain this workforce.

This is an ongoing discussion both locally and at state and national levels. The layers of opportunity to increase access to this career field are multifaceted. While we know much must be addressed in policy, we also agree there is work in our own Pierce County community that we can do to collectively elevate and strengthen this workforce.

We are fortunate in Pierce County to have practitioners who are dedicated to improving the lives of children, adults, and families and are invested in continuing to bring skilled practitioners to the field. Our region can look forward to the upcoming release of the Pierce County Behavioral Health Workforce Report for a detailed assessment and recommendations on how we can collectively move forward together. WorkForce Central stands ready to invest in and elevate these pathways to ensure we have a thriving behavioral health workforce for decades to come.